Photographers on Photographers: Suzanne T. White in Conversation with Roger Ballen

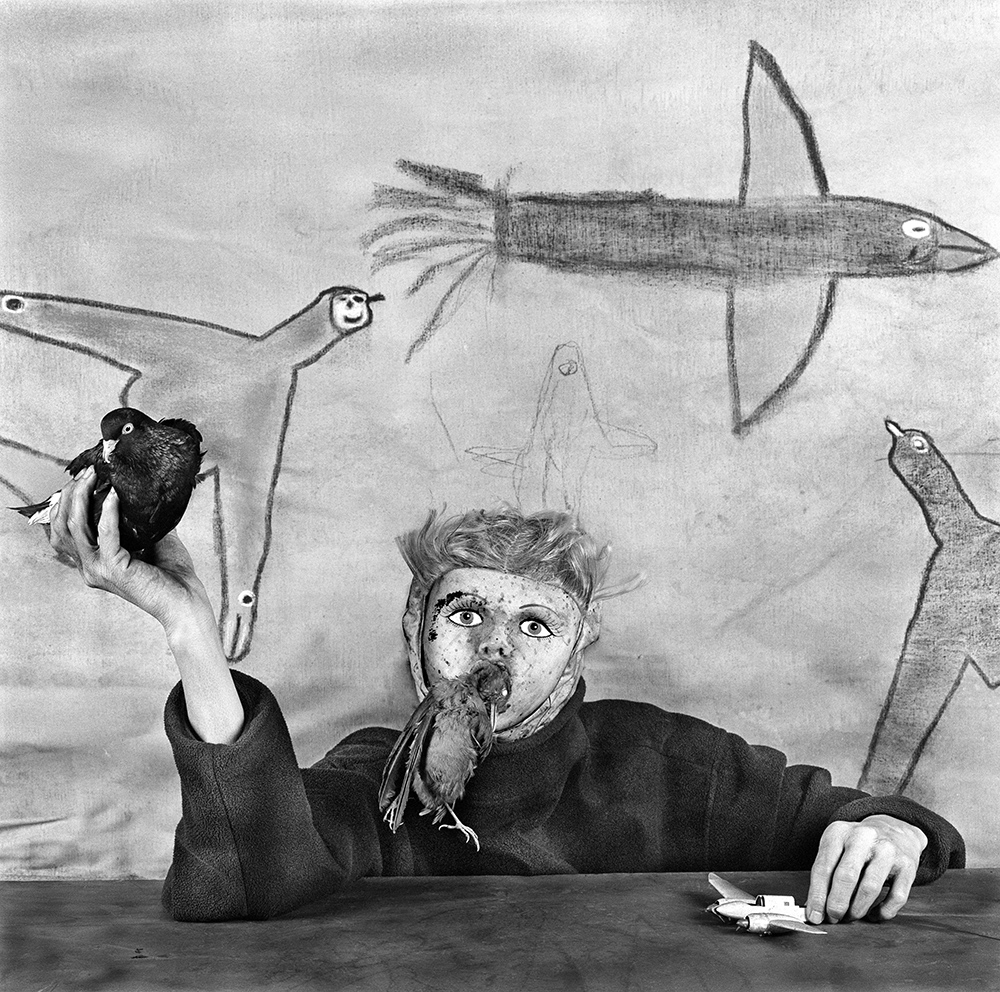

Courtyard View, 2001

Roger Ballen generously took the time to speak with me via Zoom from South Africa. It was truly an honor to interview him as I have been a fan of his for a long time. His work reaches into the psyche, it is deeply disturbing while also embracing the absurd. He depicts, constructs, and documents interiors, creating existential psychological dramas of people and animals that live on the edges of life, where we can experience through his art our alienation from the natural world. For me his work reaches into my dreams and speaks to my deep fears for the future of our planet while provoking the viewer to see the many layers of human existence. But I also feel humanity and hope when looking into his many layered photographs. Roger Ballen’s works span over 50 years. I highly recommend his recent book Ballenesque – A Retrospective – if you are interested in an in-depth overview of Roger Ballen’s work and what drives him to create his world in photography, films, and installations.

Roger at Call of the Void, photographed by Marguerite Rossouw

Born in the US and based in Johannesburg, South Africa, Roger Ballen is one of the most important photographers of his generation. He has published over 25 books internationally and has collections in the most prominent museums in the world.

His most recent publication is entitled Roger the Rat and was published by Hatje Cantz in 2020. In 2017 Thames and Hudson published his book Ballenesque, Roger Ballen – A Retrospective, a major retrospective of his collected works. Recently Thames and Hudson released a second volume in paperback.

His oeuvre, which spans five decades, began with the documentary photography field but evolved into the creation of distinctive fictionalized realms that also integrate the mediums of film, installation, theatre, sculpture, painting and drawing. Ballen describes his works as “existential psychodramas” that touch the subconscious mind and evoke the underbelly of the human condition. They aim to break through the repressed thoughts and feelings by engaging him in themes of chaos and order, madness or unruly states of being, the human relationship to the animal world, life and death, universal archetypes of the psyche and experiences of otherness. Through his unique, complex visual language, and universal and profound themes, the artist has made a lasting contribution to the field of art.

Ballen has also been the creator of several acclaimed and exhibited short films that dovetail with his photographic series. In 2022, he was one of the artists that represented South African at the Venice Biennale Arte 2022.

He is also the founder and executive director of the Inside Out Centre for the Arts in Johannesburg, which opened to the public in March 2023. The Centre aims to promote an awareness of African related issues through exhibitions and educational programmes. Its first show, entitled End of the Game, explores the decimation of wildlife in Africa both through historical artifacts and Ballen’s photographs and installations.

Instagram: @rogerballen

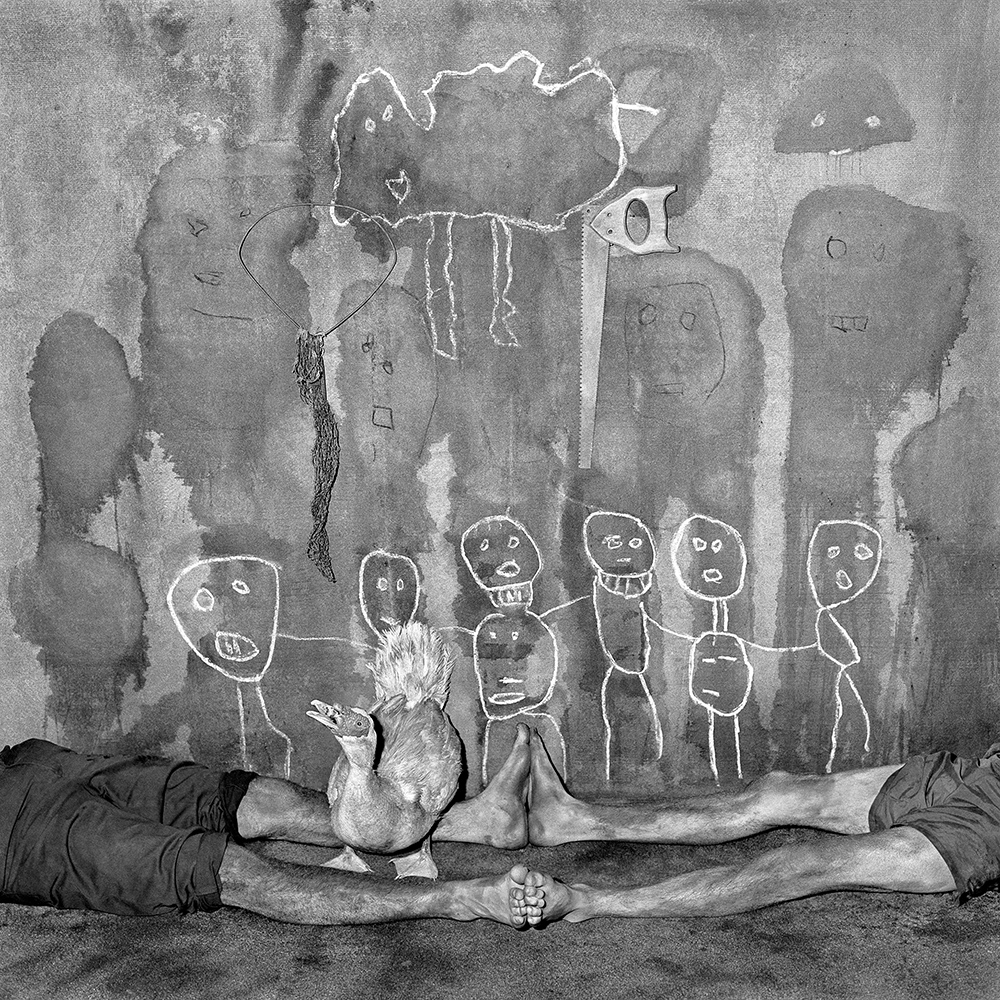

Boarding House, 2008

Suzanne T. White: Roger, it is a pleasure to meet you. Thank you for taking the time in your very busy schedule to meet with me. When you look back on your long career, what are some of the pivotal moments both creatively and professionally?

Roger Ballen: Well, see I’ve never really thought of it as a profession. Rather, it is the creative process, which is automatic and ritualistic, like brushing my teeth. I don’t think about how I should or shouldn’t do it or why I am doing it.

Photography has been a fundamental passion for me since the ‘60s. I think that my mother’s working for Magnum had a significant impact on me. She started one of the first photo galleries in America which represented Cartier Bresson, Bruce Davidson, and Elliot Erwitt, among others. My mother was friendly with these inspiring figures, and they often came to the house. They gave her books and pictures and came over for dinner. I learnt from them by osmosis and these lessons created a foundation for the work I continue to this day.

If my mother hadn’t been involved in this business, there would have been almost zero chance that I would have ended up this way. This is because photography was somewhat obscure. In fact, if you think of photography during the ‘60s or before, it was considered to be a documentary medium and was not seen as an art form. It was also hard to make a living as a photographer and the focus was rather about the people and the places that could be marketed through magazines and maybe occasionally a TV program. It wasn’t considered a way into the mind, a journey into the self.

After my mother died in 1973, I hitchhiked from Cairo to Cape Town and after that from Istanbul to New Guinea. It was a 4–5-year trip and I concentrated on photography. I completed my first book – ‘Boyhood’. That was another essential step in my career because I finally compiled a body of work in a book.

I moved to South Africa in ’82 after getting a PhD in geology. After that, I started traveling the countryside working on a project called ‘Dorps’ which means ‘small town’ in Afrikaans). I knocked on a person’s door and was invited inside. That was a turning point. I discovered interiors and the motifs, such as drawings and wire on the walls, that became the foundation for what I call the style of the ‘Ballenesque” – motifs that I would work with for the remainder of my career. I also encountered character types that would dominate my imagery. It was a pivotal moment. I often say it was the most important period of my career. I photographed the outside world for the last time.

STW: You have had a long and successful career. I am very interested in the trajectory of your work. Your recent installation ‘The Call of the Void’ fascinated me. Could you describe how you got to this recent work?

RB: The ‘Call of the Void’ is the title of my show at the Museum Tingley in Basel. Tingley was very interested in going into scrap yards to find objects that no longer served a purpose and building things. That was interesting to me. I am always trying to find things that don’t necessarily belong together and in making them belong together in a new way. This juxtaposition of seemingly incongruent elements shifts the viewer’s consciousness. It takes the spectator’s mind on a journey in another direction, which is important in art.

The concept of the ‘void’ has captivated me since my early 20’s. It is an existentialist idea that ignites questions such as: What is my purpose? Where am I going? What am I doing? Does my work have meaning? Absurdity is another crucial aspect of my work. I’ve been involved in ‘Theater of the Absurd’ for years, and the absurdity comes from the void, the idea of death. The void is the main driver of consumerism. It is the main driver of depression. It’s the main driver of religion. It’s at the core of human anxiety.

STW: That’s very interesting to me. You’ve said that you are inspired by the natural world, yet your work speaks to the dark side of human nature and its constructs, our shadow selves. Can you speak about your love of the natural world and how this connects to your work as a photographer?

RB: My ideal has always been nature, whether looking at a tree or flower or a lion or a sunset. Nature is holistic. For me, it is not disjointed. There is harmony in one way or another, and this is ultimately inspiring.

I always say I don’t need to go buy an expensive piece of art. I just look at my tree outside. I do not necessarily need art to tell me about something deeper in life. The tree tells you everything. Watching the tree in the spring, in the summer, and the fall, it has everything and it’s alive. For these reasons nature is the ideal for me.

There is no sense of harmony in my photographs. Instead, there is a conflict between the human and the animal. The psyche is disoriented. It’s chaos that rules. In fact, I suppose my pictures could be considered ‘anti-nature’.

If you worry about the consequences of what’s happening to the planet, then you try to make a statement about what is behind this chaos and disruption. The human condition has led to our current crisis and to this environmental estrangement. These are things I have always been interested in.

STW: That leads me to the question: what has living in South Africa brought to your work?

RB: Firstly, I don’t know what my work would have been if I had ended up in America or in China – anywhere else really. South Africa was like a backwater, a faraway place. When people ask me what inspires me, I look back to when I was traveling and watching lizards on the ceiling eating insects – or looking at a wall – nothing – inspired me. A blank wall inspired me. There is nothing, I don’t need to be inspired. In essence, you have to be inspired by what you are doing. If you are not inspired by your work, you are really in trouble. So, what has inspired me? My own pictures.

South Africa is a very interesting country. It is very African and it’s also European. It is also colonial and some parts of it are almost American – aspects of the country are very disjointed.

There is a lot of poverty here and the cultural differences are extreme. I think that being kept off balance in some way or another by this place – being a foreigner here – created and educated me to find a new way of trying to make sense of the world. But most of it was internally driven and one thing led to another. It was ultimately a journey into Roger’s self. My work was never driven by cultural issues, my work is psychological and existential. It grapples with the human experience. How did I get here? Through my work I dive into my own condition. It is a very mysterious journey.

STW: If you were to sit down for dinner with four other photographers, dead or alive, who would you include and what draws you to these artists?

RB: To tell you the truth, this is a hard question for me. There are many people in my career that played a big role. I’d like to go back to the beginning and talk about what was important to me because it was key to my development.

Most importantly it was Kertész. Kertész taught me that photography could be art. There was nobody else thinking that way, except maybe Cartier-Bresson. Cartier-Bresson taught me what I think of as the most important concept in photography, which is the decisive moment, freezing time. You look at something and you believe in this special moment.

Then there was Paul Strand. Paul Strand taught me about composition. He really composes pictures well. There is something coherent about the way he created what he did. There was also Elliot Erwitt who taught me about absurdity. So, these four photographers created a foundation for me. To this day I have a strong admiration for what they did.

STW: You are drawn to environments and people who live on the edges. The human subjects in your photographs are not objectified and instead present themselves as collaborators. How is it you have been able to slip into these worlds and what do you think it is about you that puts your subjects at ease? It looks like being in front of your camera is a safe place.

RB: You’re right about that – the people. Each one of these series has been in a different place, like the Shadow Chamber building, the Boarding House, the Asylum of the Birds. I have been in some of these places for years, so it is important to understand that things aren’t simple and there is a real edge to life. Johannesburg is one of the most violent cities in the world and the police are lacking in a lot of ways. This means that if you are in these types of places, it is crucial that you have a good relationship with the people who live there. There better be trust. Everyone’s got to feel wanted and at ease.

The relationship is a two-way street. I try to be there for them – whether they need a coat, or they need to go to the doctor, or they want a picture of their mother, or this or that. I do not see myself as being above people. I stay on their level and empathize with them. If I can help in some way or another, then I do that. I guess it is part of my nature. I don’t go into these places and try to manipulate a situation. I like the people, they like me, and they can see that we are genuine and care about them. Building relationships with people is second nature to me. I end up in these places because I like them. I feel comfortable with them. I sincerely like the people. Many of them have kept in touch for over 20-30 years. I get calls every day.

STW – You have a strong, distinct, prescient vision. One can look at thousands of photographs and know exactly which ones are yours. Can you speak to that vision? And has it, in terms of your point of departure, evolved over time?

RB – There’s no point doing things because you’ve always done them that way. Each picture becomes different, and you build on what you do. That is how you evolve. A lot of artists just repeat the same thing because they might have been successful, and then they can’t extend beyond that. That is not the way that I like to work. I want to build on what I do. The pictures lead me in different directions. The fingerprint never changes. But in some ways, it gets worn out or improved, it progresses in one way or another. What is important is the artist’s essence.

It is this issue of core versus experience. The core isn’t enough to be able to take great photographs – it is 50 something years of building on an aesthetic – you learn from this aesthetic. It helps you to create other aesthetics. If you don’t do the work, then you don’t go anywhere.

The key is that I’m disciplined about what I do. I’ve been focused about what I do and am very passionate about what I do. I’ve made sacrifices on all levels to get here. It didn’t come from running from one gallery to the next, from going from one bookstore to another. My evolution came from going out and doing the work year after year, day after day, day after day, after day. That is the hard part of the job. The easy part is looking at work or buying a new camera. The hard part is getting the pictures. One must persist with developing a theme from the work that ultimately is more than just a singular picture. It requires the maturation of a whole body of work that deals with a particular issue, aesthetic, reality, whatever you want to call it.

Photography is a very difficult medium because there are millions and billions of pictures taken. It is impossible to say anything of value. Show me something that I don’t know that my inner mind or my conscious mind isn’t aware of. Do that to me. Try to do that.

I don’t necessarily try to figure out the meaning of what I’m doing. I just go out and do it. Then if I like what I do, I understand what I did and that might be something I can build on. Then maybe a particular picture will give me the answer to something I will do ten years later. Perhaps I might find something in that picture I want to work with in the next picture. The pictures are made-up of hundreds of elements. It’s not just one thing.

Suzanne Theodora White is a visual artist with a practice that focuses on the fragility of the planet and documenting the seasonal and climatic changes to the land with a particular interest in the connection of place and spirit.

She received her BFA from Tufts University and the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston where she studied painting. She has received numerous fellowships including the Clarissa Bartlett Fellowship, William Paige Fellowship, and Kate Morse Fellowship for Women, from the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. In the 90’s she was retained by Absolut Vodka for their famous ad campaign. Her work is informed by her experiences traveling the globe, from surveying bird populations in the Amazon, to an 18-month solo expedition overland around the world. Currently she is pursuing an MFA from Maine Media Workshops and College.

During the last year she has shown work in exhibitions around the country and Europe. Her photographs and paintings have been published in Forbes, Connoisseur, and the New Yorker. She lives and works in Maine.

Instagram: @shepherdess1

Comments are closed.